The economic benefits of EU accession are many and significant, but not all are irreversible: something that eurosceptics in Central and Eastern Europe would do well to remember.

More than 15 years after the first wave of eastern EU enlargement we take on the challenge to (re)evaluate the long-term gains of Central and Eastern Europe’s economies from the EU accession.

- Montenegro set to enjoy emerging Europe’s highest economic growth

- Will Bulgaria and Croatia meet their eurozone accession deadlines?

- How the Pravetz 82 introduced a generation of Bulgarians to the computer

This article elaborates on the overall economic gains, measured as extra GDP per capita that can be attributed to the EU accession for the new member states over time compared to a hypothetical scenario of having remained outside of the EU.

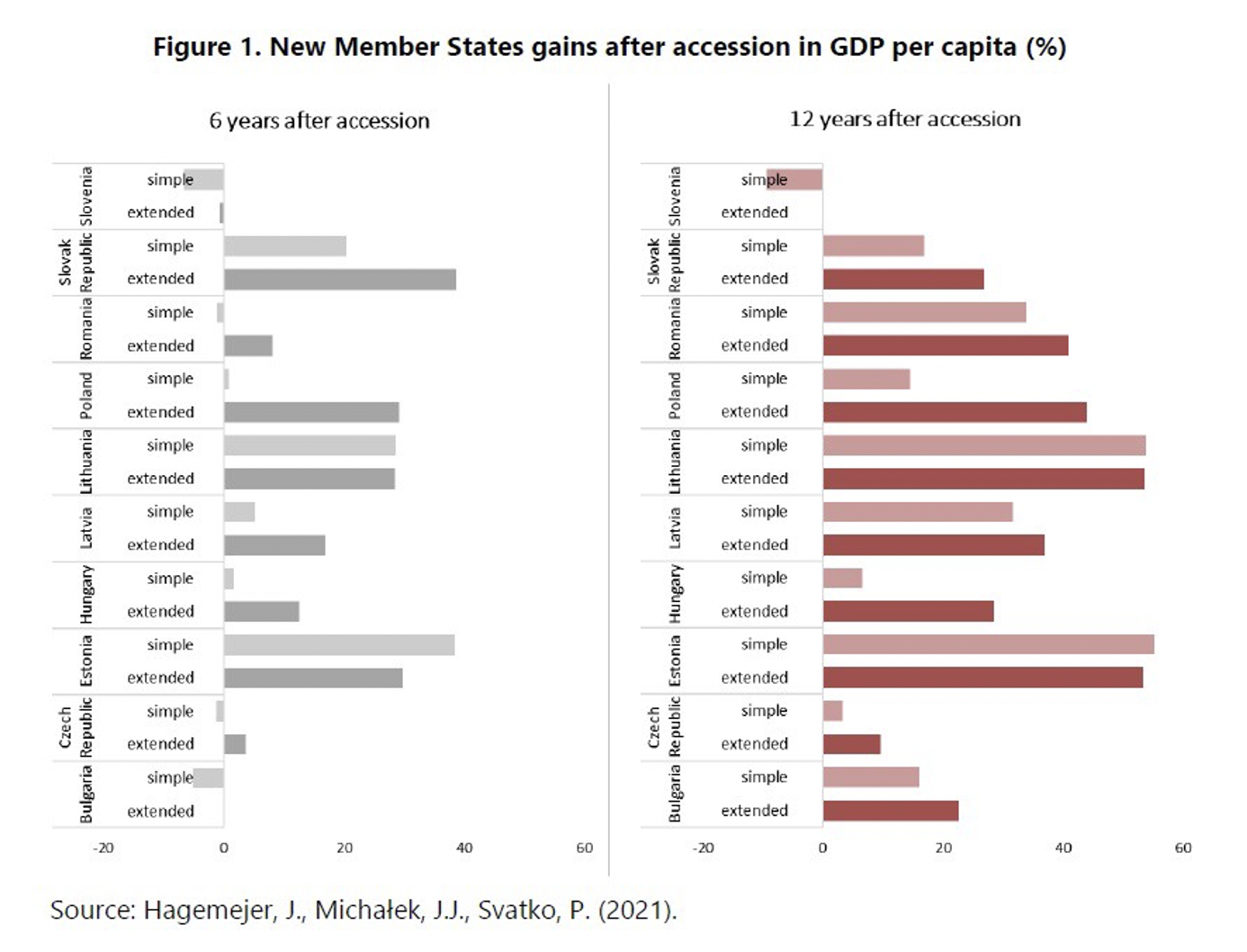

The results suggest the presence of significant gains from EU accession. More importantly, these gains appear to be long-lasting and increasing over time: for many of the analysed countries, the calculated gain at least doubled between the sixth and 12th year after accession.

For five of the 10 analysed countries, the 12-year gain in levels of GDP per capita against the scenario of no accession is at least 30 per cent.

The gains, however, have not been universal throughout all CEE economies.

In particular, they were rather marginal for countries that entered the EU with relatively high levels of economic development and decent physical infrastructure.

These include Slovenia, where the performance gain was close to zero, as well as Czechia and Hungary where the calculated gains range, respectively, from three per cent to 10 per cent and from seven per cent to 28 per cent after 12 years.

On the other hand, the gains were considerably larger in Poland, Slovakia, and the Baltic countries, exceeding 50 per cent of extra GDP per capita in 12 years after accession for Lithuania and Estonia.

What about Poland?

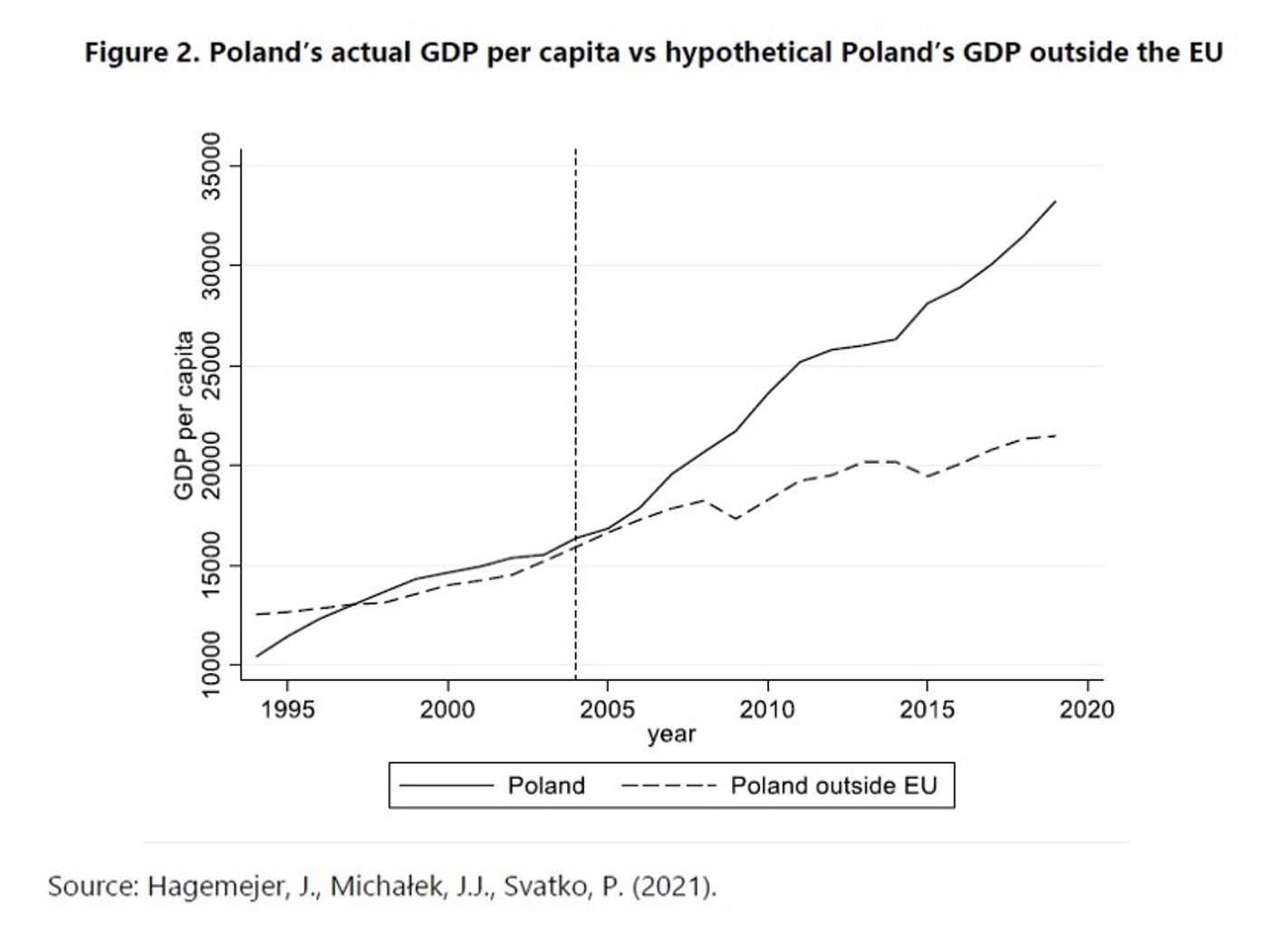

Gains in Poland have been clearly accumulating over time and stood at roughly an extra 55 per cent of GDP per capita 15 years after accession.

The “no-accession” Poland, in turn, has a persistently lower rate of economic growth compared to actual Poland. This difference in growth rates seems to even increase over time, suggesting that these are not one-off, but rather persistent, long-lasting benefits.

Construction of the “no-accession” scenario

The major difficulty in the assessment of economic gains from accession is to predict what would have happened if accession had not occurred.

Here, the synthetic counterfactual method comes in handy. In short, this method allows us to create a “synthetic country” that is a weighted average of countries that have not been part of EU integration. The choice of the countries is not random — it is based on a set of country characteristics that can predict the GDP per capita well.

Two alternative choices of variables were analysed for the creation of the synthetic counterfactual in the study.

First, in the simple scenario, we included structural economic variables such as the population growth, share of industry in total value added, the share of agriculture in total value added, share of investment in GDP, the level of real GDP and secondary and tertiary schooling indicators. The second, extended version, of the model, additionally included several institutional variables related to the level of economic freedom in the country (i.e., tax burden, business freedom, monetary freedom and trade freedom indicators).

These additional variables were assumed to reflect both phenomena: progress in the transition process and that of the accession to the EU. The choice of the model matters for the results with overall higher estimated gains found in the extended models.

The composition of synthetic “no-accession” country was different for each analysed new member state — Australia, Belarus, Korea, Macedonia, Russia and Ukraine being often part of that construct. Alternative choices included Albania, Algeria, Brazil, Chile, China, Indonesia, Macedonia, New Zealand and Switzerland.

Economic and political reforms during the accession period

The EU accession experience of CEE was very different from that of western European countries and unfolded alongside profound political and economic transformations of the early 1990s.

The initial “Europe Agreements” enabled creation of free trade areas and put forward the expectations on the future structural reforms, including an approximation of legal systems. The so-called Copenhagen Criteria introduced in 1993 has further underlined the need for prospective member states to have stable democratic institutions that could ensure the protection of the EU’s fundamental values as well as functioning market economies as competitive members of the Single Market.

While it was assumed that all future members of the EU should fulfil the Copenhagen Criteria, the actual speed of transformation and implementation of much-needed reforms was somewhat differentiated among the acceding countries at the time.

There is no simple answer about the extent to which the transition reforms were “imposed by” and/or “resulted from” the accession strategy. One may conclude that even in the case of the “Big Bang” strategy of reforms, the creation of the rule of law state would not have happened automatically. The external pressure, in the form of pre-accession commitments, facilitated the transition process and creation of the rule of law institutions.

Why is this still relevant today?

The results presented in the study provide yet more evidence on the substantial gains from EU accession.

This is particularly important for the countries aspiring to become members of the EU, and shows that adherence to the requirements of several structural and institutional reforms pays off in the long run.

In light of the rise of euroscepticism in the new member states, it is also important to note that some of these gains are reversible, in that they stem from access to the Single Market and the inflow of foreign direct investment from the EU-15 which is largely conditional on EU membership.

On the other hand, the improvement of infrastructure through structural fund has already been rather advanced and is not likely to play a major role in the development of most of the NMS. However, new initiatives (such as the EU Recovery Fund) provide a sustained source of benefits from the EU membership for the newcomers.

In the case of the CEE countries, the anticipation of political and economic gains from alignment with the EU and its values was a motivation for accelerated implementation of democratisation reforms, which explains the successful transitions in these economies.

While it can be an important lesson for other countries from the region, it is also crucial to understand that these reforms were also required to support a smooth transition to a market economy. Consequently, their reversal could jeopardise the potential for reaping gains from EU membership and further integration.

This article, co-written by Jan J. Michałek, professor at the University of Warsaw, is based on a paper: Economic Impact of the EU Eastern Enlargement on New Member States Revisited: The Role of Economic Institutions; Hagemejer, J., Michałek, J.J., Svatko, P. (2021). Central European Economic Journal, 8(55), 126–143. DOI: 10.2478/ceej-2021–0008. The results are summarised here with permission from the journal editor.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment